SAN DIEGO —

It was a mild May evening in 2020, still in the grim early weeks of San Diego’s pandemic year, when gunshots broke the late-night quiet on Winona Street.

A group of men — up to seven, witnesses would later tell police — had gotten into an argument. The gunfire had prompted three 911 calls to police around 10:30 p.m., and when officers arrived, evidence of the crime was spread out over several blocks.

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

One victim was found on Winona Street near the spot of the shooting between University Avenue and Wightman Street. A second was found at the intersection of 50th Street and University Avenue, and a third a short distance away on 49th south of University.

The injuries were not life-threatening, the men shot either in an arm, leg or, in one case, both. A quartet of men believed to be the assailants fled. No arrests were made.

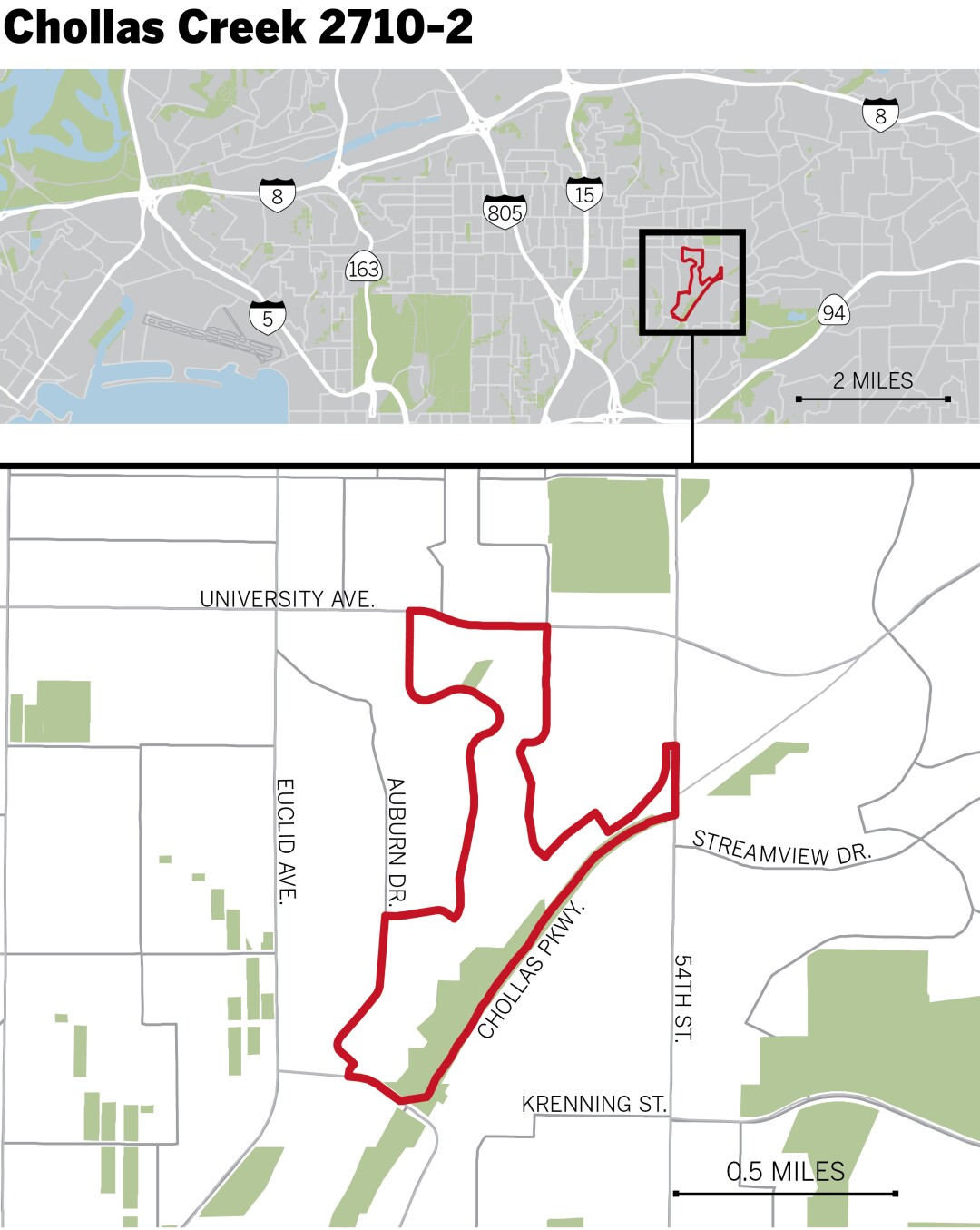

The shooting on Winona would not be the last violent incident for this neighborhood, wedged between Chollas Parkway, University Avenue and Euclid. It was one piece of a startling increase in violent crime in this diverse neighborhood of 2,700 people during the pandemic year.

An analysis by The San Diego Union-Tribune of crime data in the city of San Diego from 2019 through 2020 showed the Chollas Creek neighborhood had 20 violent crimes in 2020 — a 300 percent increase from 2019, when the area had a total of five violent crimes.

It was one of many neighborhoods in the city that saw an increase in violent crimes in 2020, compared to 2019, the analysis showed.

Overall, violent crimes in San Diego — defined as murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault and strong arm robbery — increased 2.4 percent in 2020 from 2019.

Across the city the analysis showed that 31 percent of the roughly 800 block groups had an increase in violent crime in 2020. But another 35 percent saw a decrease. And one third of all neighborhoods in the city saw no change.

While violent crime in the city increased in 2020, it did so at a far lower level than the nation as a whole. Last month, the FBI reported that violent crime increased 5.8 percent nationally in 2020 — more than twice the increase seen in San Diego.

“I’m actually surprised it didn’t go up more with everything we were facing,” San Diego police Capt. Dan Grubbs said.

The Union-Tribune’s analysis also looked at a selection of nonviolent, lower-level crimes, again comparing the pre-pandemic year of 2019 to 2020.

These crimes — larceny, residential burglary, fraud, commercial burglaries, malicious mischief and some domestic crimes — fell 3.8 percent.

San Diego police officer Jordan Williams investigates an incident where about 12 cars were damaged near 14th and J Streets on Friday, Oct. 8, 2021 in San Diego, CA. Officers said the suspect was in custody. Crime has increased in the area and through the city.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

The 2.4 percent increase in violent crime as calculated by the Union-Tribune is slightly more than the city police’s own calculation announced in March that said violent crime increased 1.7 percent in 2020 from the previous year.

The difference stems from the way the Union-Tribune collected and analyzed crime data.

The San Diego Association of Governments, known as SANDAG, provides crime information that reflects how reported incidents change over time. For example, a crime initially reported as a simple battery could, days or even weeks later, be upgraded to an aggravated assault. Meanwhile, police data typically calculate totals and changes in crime based on how they are originally reported.

The Union-Tribune’s analysis also removed any incidents that occurred outside city limits, regardless of whether the San Diego Police Department responded to or reported a crime in its overall total.

The Union-Tribune opted to analyze crime by census block groups — small portions of census tracts that generally have between 600 and 3,000 people — to focus on how residents of smaller neighborhoods are impacted by crime and police presence.

Like many other police agencies, the San Diego Police Department typically does not analyze or report crimes by census block groups. More often, the department reports by patrol beats in each of nine geographical divisions, which are larger areas than census block groups. Neither method is inaccurate.

San Diego police investigate a double homicide at a high-rise apartment in East Village on Thursday, Oct. 21, 2021 in San Diego, California. Ali Nassar Abulaban has been charged in the murder of his wife Ana and her friend Rayburn Barron.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

The analysis revealed San Diego crime in 2020 tracked national trends that showed specific crimes of violence increasing, while property crimes and other nonviolent crimes decreased.

In San Diego homicides increased 8 percent, from 50 in 2019 to 54 in 2020. While a noticeable jump, it was far less than in other places.

Nationally, the FBI reported that homicides soared 30 percent in 2020 from the year before, the largest single year increase ever recorded by the agency.

A study by the Council on Criminal Justice of 34 cities, including San Diego, showed homicides rose in 29 of the cities. In Chicago, homicides increased 55 percent; in New York City, they increased 43 percent.

Aggravated assaults increased 9 percent in 2020 in San Diego. That was higher than the Council on Criminal Justice findings, which showed aggravated assaults up 6 percent.

Metal bars are used as security for businesses on the corner of El Cajon Blvd. and Winona Avenue in City Heights on Wednesday, Oct. 6, 2021 in San Diego, CA. The city has seen an increase in crime.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Experts agree that the lockdowns and resulting economic shocks that shuttered businesses and threw people out of work likely influenced some crime trends. But they cautioned it is difficult to attribute increases, or decreases, in crimes in a given year to a single cause.

“The effects are not all that straightforward,” said Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist and professor at the University of St. Louis-Missouri. “The sheer stress and strain of the pandemic undoubtedly pushed violence up somewhat. Also, criminologists tend to distinguish between motivations to engage in crime and opportunities to do so.”

For example, residential burglaries in San Diego fell nearly 14 percent in 2020. That makes sense — and tracks national declines for that year — because of stay-at-home orders in the spring of 2020 that kept people inside, Rosenfeld said.

Larceny of less than $200 declined nearly 16 percent. Larceny over that amount was down, too, by 7 percent. Meanwhile, commercial burglaries increased 12 percent, the data show.

Most larceny charges involve shoplifting, Rosenfeld noted, and with nearly all retail stores closed or open only reduced hours during the pandemic, the opportunities to shoplift diminished. That would explain the decline.

Meanwhile, closed stores made tempting targets, day or night, for burglaries.

Stuart Terry has had his automotive business on the corner of El Cajon Blvd. and Estrella Avenue since 1986 and has dealt with vandalism for more than two decades in City Heights on Wednesday, Oct. 6, 2021 in San Diego, CA. Terry said in the 80s and 90s he didn’t see graffiti on his business but that has changed. The amount of graffiti varies, sometimes it’s multiple times a week or month. He mentioned a time he hired one of his employees to paint over the graffiti but as soon as the employee washed the paint brushes clean, it had been painted over again.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

In San Diego, malicious mischief crimes — vandalism, graffiti and the like — increased by nearly 15 percent from 2019, more than any other crime analyzed by the Union-Tribune. That, too, could have been driven by pandemic closures that idled workers, students and others for weeks on end.

Grubbs, who oversees the Police Department’s Central Division, which covers downtown San Diego and surrounding neighborhoods, said robberies and rapes decreased in the areas his officers patrol because a hotbed of those crimes — the Gaslamp Quarter — turned into a ghost town for some time.

“With the Gaslamp closed during COVID, we had a dip in those incidents,” he said, “and then as things reopened, we saw that rise up.”

On the other hand, commercial burglaries went up “because people started going after all the closed businesses,” the police captain said.

Pandemic Impacts

Downtown’s bustling Little Italy neighborhood is home to restaurants, shops and a growing residential population of about 4,000 residents, according to 2019 data from the U.S. Census Bureau. About 60 percent of them are under 35 years old.

People stroll in Little Italy on Tuesday, Oct. 19, 2021 in San Diego, California.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

The destination spot for diners, tourists and conventioneers was hit with a 70 percent increase in violent crime in 2020 from the year before. In 2020 there were 46 violent crimes reported there, up from 27 in 2019.

That 70 percent increase in crimes was largely fueled by aggravated assaults that nearly doubled, from 15 in 2019 to 28 in 2020, and strong-arm robberies that nearly quadrupled from three to 11.

Marco Li Mandri, head administrator of the influential Little Italy Association, said he believes the increase is largely due to the concentration of unsheltered people who live downtown, as well as pandemic-related policies in the criminal justice system.

“I think it is the impact we had from the courts, as well as the prison population release,” he said.

That theme of larger social forces amplified by the pandemic has been sounded by critics around the nation as the crime statistics emerged. Those analyses often point to social justice protests in the wake of the George Floyd killing, and to the economic stresses on individuals from business shutdowns due to COVID, contributing to crime increases.

Critics also suggested policies in California and elsewhere that sought to reduce populations in jails and prisons, where the virus could spread easily, were to blame.

Marco Li Mandri, head administrator of the influential Little Italy Association, said that there is an increase in “disorder not crime,” and that the area is still safe on Monday, Oct. 25, 2021 in San Diego, California. Little Italy is a destination spot for diners, tourists and has a population of about 4,000 residents.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

In order to lessen populations in jails and prisons, state officials ordered the early release of at least 11,000 prisoners, largely nonviolent offenders who had less than a year to serve on sentences.

At the same time, the state courts instituted an emergency rule that set bail for all but a handful of serious crimes at $0. The result was a 30-year low in the state person census and plunging local jail populations, though the jail population climbed again a few months later before leveling off below pre-pandemic levels, according to the Public Policy Institute of California.

San Diego police Capt. Manny Del Toro, a 31-year veteran of the department, said some criminals — he singled out thieves — were brazen because of the limitations that prevented officers from booking them into jail. A vehicle theft, for example, was not a crime that landed a suspect in jail.

The changes in booking rules also impacted the homeless population. Del Toro said officers were unable to jail unsheltered people in connection with crimes like illegal lodging.

Capt. Manny Del Toro walks through an area where a shooting happened in September that left one man dead and another person was injured outside of Mike’s Market in Mountain View neighborhood on Monday, Oct. 25, 2021 in San Diego, California.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

The police captain said he saw other COVID-19 impacts on crime, too. He said the county Probation Department cut back on home visits to curtail the spread of the disease. “Individuals who would have been in violation of probation were basically left unchecked,” he said.

Yvette Urrea Moe, a spokeswoman for the Probation Department, said cases were screened and if any warranted “more intense intervention due to immediate serious public safety risks,” then officers took steps such as home visits and arrests. Otherwise probation officers turned to phone calls, video calls and emails to check in on probationers.

While inmate releases and less punitive policing are frequently targets of critics alarmed by increases in violent crime, Rosenfeld said that is not supported by data nationally. His group compared cities that had some sort of bail reform measures in place in 2020 with those that did not and saw no significant differences.

“We looked at jurisdictions engaged in bail reform, and we looked at cities with progressive prosecutors, and we found the thing about increases in crime is they are so consistent across so many cities,” he said. “Violent crime was up across the board.”

A bullet hole from a shooting that happened in September that left one man dead and another person injured outside of Mike’s Market in Mountain View neighborhood on Monday, Oct. 25, 2021 in San Diego, California.

(Ana Ramire / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Other factors outside the criminal justice system may have also contributed. The pandemic not only closed businesses and schools, but also hampered the work of violence intervention and social services groups and community organizations that provide programs and other services, said Cynthia Burke, the director of research and program management at SANDAG and a longtime expert on local crime trends.

“There is just so many factors that go into this,” she said, adding that the pandemic year will have long-term effects on crime trends. “A lot of social services providers were just not open, and that has an impact.”

Cynthia Burke, director ofresearch and program management at the San Diego Association of Governments (Eduardo Contreras / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Eduardo Contreras/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Neighborhood Struggles

Two side-by-side block groups in East Village that run south of Market Street and are bounded by Park Boulevard on the west and Interstate 5 freeway on the east, saw violent crime plunge — by 11 percent in one neighborhood, and 21 percent in the other.

These are both areas that have been plagued by violent crimes over the past several years, with a total of 453 crimes since 2019, including four homicides and 285 aggravated assaults, the data show. Though the decline was welcome, the neighborhood still felt the impact of a grueling year.

Alexandra Branton works at Amplified Ale Works, on the corner of Island Avenue and 14th Street.

Because of vehicle break-ins, she tries to avoid parking on certain blocks. “When you work down here, you know which streets aren’t good, and even then sometimes you have to risk it anyway,” she said.

A resident who shared only her first name, Sofia, said fewer residents were out and about last year — “It was completely dead,” she said — and, in turn, there were visibly more homeless people on the streets and in spots where they wouldn’t usually set up tents and other makeshift shelters.

Branton agreed.

Then there were the protests. Over the course of several months, protesters flooded the downtown area to denounce racial injustice and police violence. Residents said police would block off areas and that it was hard to spot officers anywhere beyond the front lines of the protests.

Alexandra Branton, 26, works at Amplified Ale Works and said she doesn’t park on certain blocks because of car break-ins on Friday, Oct. 8, 2021 in San Diego, CA. Branton said she has had her car broken into twice.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Now there’s more of a visible presence of police, said Sofia, who lives in a high-rise apartment building on Island Avenue between 15th and 16th streets. “Now you see them driving around, walking around on streets,” she said.

Even after the protests tapered off, Branton said, police often took a while to respond to calls in the area.

“I get it, not all of it is an emergency, but I just think they’re so used to things down here that they’re kind of desensitized to it, so they don’t take everything super seriously,” she said. “Anytime we’ve ever called the cops here, they take forever to show up, like 45 minutes to an hour minimum. So at that point we don’t even call half the time.”

Grubbs, the captain in Central Division, said last year’s spate of protests targeting racial injustice and police violence impacted the operations of the police force. Officers worked longer shifts during the height of the protests, a period of about five weeks when protesters were marching by the thousands, and officers responded only to major emergencies when the protest were happening.

“That affected our services,” he said.

Grubbs also said that 12 to 14 officers from his police station at a time were out on medical leave because of injuries they sustained during protests or unrelated violent encounters. He said officers faced hostility from some community members they encountered.

“People were just losing their minds on officers,” he said.

Rosenfeld, the criminologist who has studied crime and violence trends for years, said that analysis of recent data has shown that the increase in violent crime is largely concentrated in underserved neighborhoods that have been affected in the past by violent crime.

“The increase tends to be concentrated in the very neighborhoods where violent crime is traditionally generally higher,” he said.

Even in neighborhoods where there was no increase in violent crime in 2020, residents still felt the impacts of violence.

Verlie Hodrick “Big Junior”, 74, has lived on Magnus Way for 25 years and said that crime in the area increased last year, the same time his second cousin, Michael Bowden-Fowler, was shot and killed across the street from where he lives. Hodrick said his house was shot up too but things have calmed down since the shootings on Tuesday, Oct. 12, 2021 in San Diego, CA. Hodrick said Bowden-Fowler was a good kid. “He was trying to make something out of himself,” said Hodrick

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

On Dec. 12, 16-year-old Michael Bowden-Fowler was shot to death outside a home on Magnus Way in Lincoln Park. It was one of a flurry of shootings on the residential street that rattled this block group, defined by Interstate 805 on the west, Euclid Avenue on the east, Logan Avenue on the north and Beta Street on the south.

Detectives marked bullet holes in homes to differentiate between gunfire tied to the homicide and older shootings, said Del Toro, who oversees the Southeastern Division police station. The area includes the neighborhoods of southeastern San Diego, which tallied 16 homicides in 2020 — about 30 percent of the total for the city, according to data from the Southeastern Division.

The Magnus Way neighborhood had 18 violent crimes in 2020, the same number as the year before. Residents said the outbursts of gunfire, many of them drive-by shootings, were tied to a couple of houses where people would gather out front during the pandemic.

“It was scary,” said a resident who did not want to provide her name. “It was very scary. Didn’t know what was going to happen.”

She said a stray bullet once pierced a window and a car in her garage.

A gun detection system known as a ShotSpotter connected to a light pole on Monday, Oct. 25, 2021 in San Diego, California. The detection system alerted the police dispatch center to a shooting where 16-year-old Michael Bowden-Fowler was killed. San Diego City Council has delayed renewing a contract with the company.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Gunfire struck other homes, including a neighbor’s house a few doors down. The neighbor, who did not want to be identified in this story, said that on one occasion, a stray bullet came through his living room window while he was home. He was not hurt.

The man, a widower who is retired, said he believes job loss and lockdowns prompted by the pandemic contributed to the violence. “People were spending a lot of time around, hanging out here in the street,” he said. “While everything else was shut down, they had no place else to go, so they’d come down here and hang out.”

A neighbor, Bitina Lopez, a mother of five children, said she doesn’t allow her children to go outside on their own.

“You get scared that there could suddenly be gunfire,” she said.

A memorial for a man who was killed on Paradise Valley Road in 2019 on Monday, Oct. 25, 2021 in San Diego, California. Joaquin Ruiz was found shot in his car on July 12, 2019. Three men have been arrested in his death.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

The jump in violent crime in San Diego and nationally in 2020 should be taken with some caveats, said Jesenia Pizarro, a professor at Arizona State University School of Criminology and Criminal Justice. She said 2019 was a historically low year for crime nationally, so increases should be measured against that lower starting baseline.

At the same time, she said violent crime was inching up, slowly, before the pandemic though still at historically low levels.

“It didn’t just pop up this year,” she said. “As far back as two years ago before the COVID pandemic we started seeing some jurisdictions experience more violent crime. Once the pandemic hit and then the lockdowns, these small upticks suddenly magnified into bigger issues.”

That trend may be continuing this year. A mid-year report by SANDAG said that violent crime increased 20 percent in the first half of the year in the city of San Diego — higher than the overall county increase of 14 percent.

Original data and further methodology can be found on the Union-Tribune’s GitHub page.

"crime" - Google News

October 31, 2021 at 07:00PM

https://ift.tt/3nIT2jJ

Crime Counts: Violent crime increased in San Diego in pandemic year — but not as much as national trend - The San Diego Union-Tribune

"crime" - Google News

https://ift.tt/37MG37k

https://ift.tt/2VTi5Ee

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Crime Counts: Violent crime increased in San Diego in pandemic year — but not as much as national trend - The San Diego Union-Tribune"

Post a Comment